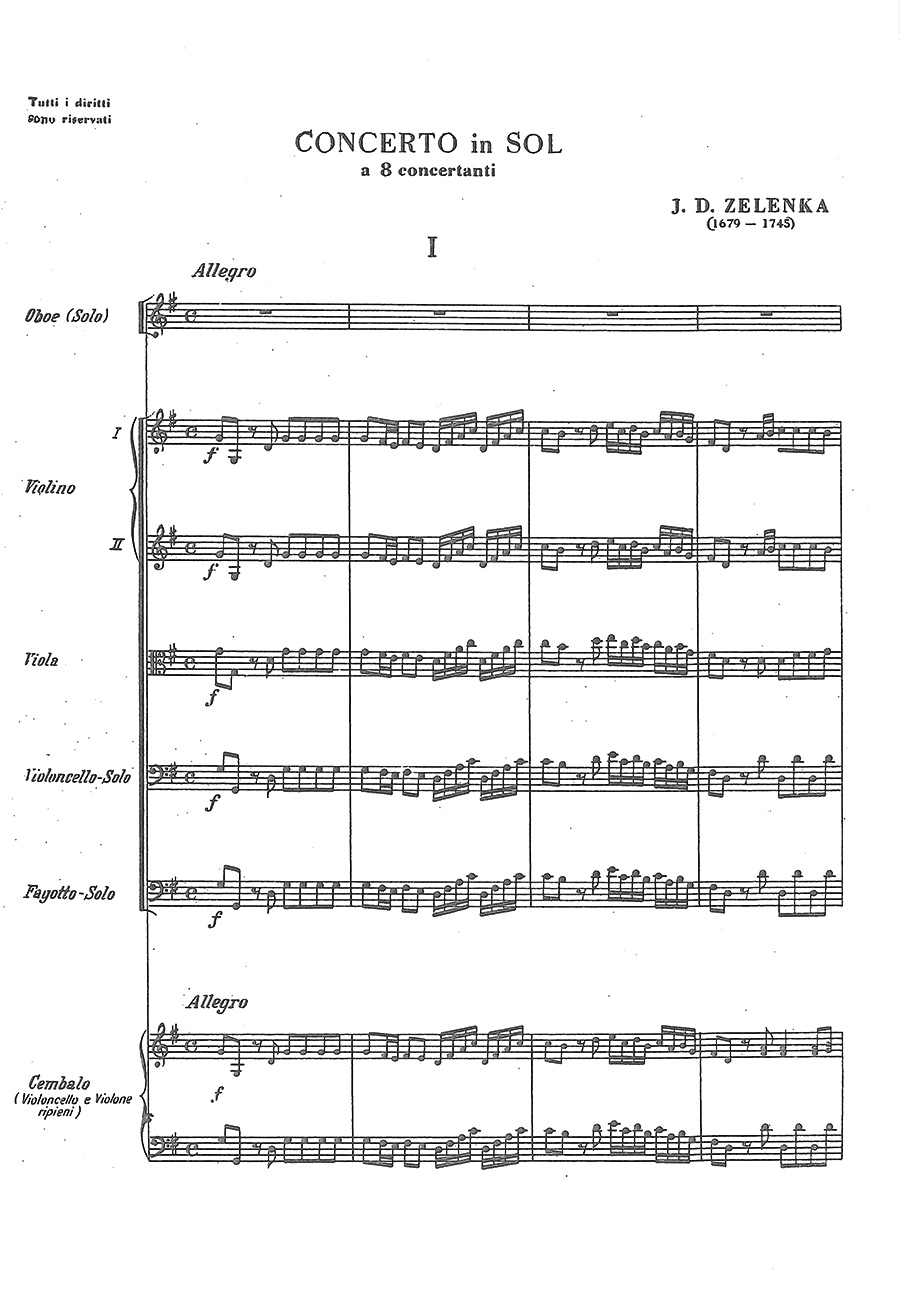

Concerto in Sol a 8 concertanti

Zelenka, Jan Dismas

19,00 €

Jan Dismas Zelenka – Concerto a 8 concertanti in G major (ZWV 186)

(b. Louňovice, Bohemia, 15 or 16 October 1679 – d. Dresden, 23 December 1745)

Preface

Zelenka’s Concerto in G major, for eight instruments and continuo, was written in 1723 at the same time as several other orchestral works from his pen: Hypocondrie a 7 in A major (ZWV 187), Ouvertüre a 7 in F major (ZWV 188), and Symphonie a 8 in A minor (ZWV 189). His other compositions for orchestra include the Capricci (ZWV 182-85), composed roughly between 1717 and 1718, and the later Capriccio of 1729 (ZWV 190).

The Concerto a 8 is preserved in an autograph score and an early twentieth-century copy with an associated set of parts, all located today in the Dresden City and State Library (D-Dl, autograph under shelf mark 2358-0-1). Its place and date of origin are given in the author’s handwritten title, “Concerti 6. fatti in fretta / à Praga 1723” (Six concertos, written in haste in Prague, 1723). This allows us to conclude that five further lost concertos were written at the same time for the same occasion, probably the coronation festivities in Prague. Still, as Wolfgang Reich has suggested, it is likely that several of these five concertos survive among Zelenka’s existing compositions, but are assigned to different genres in their original sources.

Zelenka’s term “a 8” does not refer to the number of real voices in the concerto, but probably to the eight staves in the manuscript. In fact, the piece calls for six concertante instruments: two violins, a viola, a cello, an oboe, and a bassoon. The work is laid out in the form developed in the 1720s and 1730s for the Italian solo concerto, with two fast movements flanking a slow middle movement. The earliest examples of this three-movement design are found among the solo concertos of Albinoni, Torelli, and Vivaldi, which became known in Germany during the 1720s. Indeed, the so-called “Cabinet II,” the collection of instrumental pieces played by the Dresden Court Chapel, actually contains a large number of works by these composers that Zelenka probably examined and studied.

Although the Concerto a 8 uses the modern three-movement design, Zelenka’s other above-mentioned orchestral works vary widely in structure. The Capricci derive from the Baroque suite, with a large number of dances (e.g. minuet, bourrée, allemande) alternating with movements either influenced by operatic cantabile (aria) or bearing generalized tempo marks. The total number of movements ranges between five and seven. A similar overall design is apparent in the Ouvertüre a 7 (ZWV 188), the Sinfonia a 8 (ZWV 189), and even the Capriccio (ZWV 190). Only Hypocondrie (ZWV 187) resembles the Concerto a 8 in consisting of three movements, albeit in reverse order: [Adagio]-Allegro-Lentement. The Concerto a 8 is thus all the more important for employing the modern form of the genre.

Equally adapted to modern taste is the function of the five solo instruments and their interaction in the tutti passages. Not only do they serve to enlarge on material from the main theme of the first orchestral ritornello, they also augment their standard sequential and idiomatic passages with independent motifs missing in the tutti. In this way Zelenka, following in the footsteps of Albinoni and Vivaldi, strikes a balance between the principles of integration and contrast.

Another of the work’s characteristic features is the timbral and motivic hierarchy among its solo instruments. Even where one or more concertante instruments are subordinated to two others, they nevertheless present motivic segments, often derived from the main material itself. Thus, even when overshadowed by the other instruments, they remain part of the thematic texture. Zelenka’s interest in this procedure, and his handling of themes in some solo episodes, recall the technique that Bach employed in the Brandenburg Concertos, completed no later than 1720.

We already notice an internal timbral contrast in the first movement’s opening ritornello, where the two solo violins echo a segment of the theme. In the final unisono phrase of the ritornello, Zelenka spreads a repeated triple-meter motif across two bars of the prescribed 4/4 meter. The resultant shift of accents is one of his stylistic fingerprints. Another rhythmic shift, applied to a different motivic segment, occurs in bars 114 and 115. The first oboe solo (m. 12) consists of a melody only partly compatible harmonically with the main theme of the ritornello, being half a bar longer. In reality, it forms a new thematic unit assigned to the soloist. At the same time, the continuation of the oboe entrance takes up a short motif from the main theme (mm. 14-15), distributed between the two violins and the oboe itself. Beginning in bars 15 and 16, the solo oboe entrance proves to be the start of a second exposition of the ritornello’s thematic material, this time explicitly conceived for concertante instruments (mm. 12-24).

The oboe entrance, again based on the solo melody (m. 24), constitutes the first episode (mm. 24-56), whose motivic elements, employing a procedure already familiar from Bach, are partly connected with the ritornello. Here a central role is played by a rhythmic cell formed of two sixteenth-notes and an eighth-note. The resultant melodic-harmonic sequences grant leeway to the cello and the two violins (apart from the oboe, which has been spotlighted from the very beginning) to undertake solo excursions and lead to the second tutti, this time in the dominant. The solo theme is now stated by the first violin, which takes over the main role from the oboe in the sequences and freely idiomatic passages that follow. Three successive tutti statements of the theme (in B minor, D major, and G major) lead to a sort of recapitulation consisting not only of orchestral material from the first ritornello, but also of sequences from the first episode, played by the oboe and first violin (especially mm. 37-44). The formal structure of the movement – three ritornellos and two episodes – is thus quite straightforward.

The whole of the second movement, Largo cantabile, has the character of a concerto for six instruments in which the solo parts are equally involved in developing the musical fabric. The theme, introduced by the bassoon, consists of three segments that Zelenka varies in harmonic-melodic sequences and divides among the soloists. As was then customary for concertos and operatic sinfonias, the movement ends with a Phrygian cadence played by the tutti.

The equal participation of the soloists reaches a climax in the third movement, which develops a single theme introduced in unison. Section 2 of this three-section movement contains two thematic tutti sections, the first in the dominant, the second in the relative minor. Remarkably, the theme is shifted a full beat at the opening of the recapitulation (mm. 303-06): unlike the beginning of the movement, here the first violin starts the theme on the strong beat, i.e. without a rest on the downbeat, while the end of the same solo phrase overlaps with the genuine reprise of the theme, performed by the tutti in its original rhythmic form.

Bars 30 to 35 of the finale offer a sort of cross between material typical of the episodes and thematic elements from the opening tutti. The first episode (mm. 9 ff.) contains an extended harmonic-melodic sequence in which the main role is given to the oboe. The entrance of the two violins in m. 29 leads to a new sequence consisting of imitative scales, followed unexpectedly in mm. 34-35 by a thematic segment from mm. 6-7, played unisono. The next phrase, delivered in parallel thirds by the oboe and the first violin (m. 36), begins with the same thematic segment only to continue with a new autonomous ending. As mm. 34-35 are given to the unison tutti, a timbral contrast ensues between the immediately preceding scales from the solo violins and the tutti itself. Here the attraction of the compositional fabric lies in the structural nature of this contrast, namely, in the exchange of motifs between the ensembles: the sequence elides with the thematic segment, which in turn elides with the next sequence beginning at m. 39, thereby merging the contrasting materials. In this way Zelenka reveals a thorough grasp of a basic question of the concerto genre, one for which Bach found his personal solution in the Brandenburgs: how to reduce the motivic contrasts in the material of tutti and concertino.

Translation: Bradford Robinson

For performance material please contact Universal Edition, Wien. Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich.

| Score No. | 1285 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Pages | 60 |

| Size | |

| Printing | Reprint |