Die Spinnerin Op. 192, Die Libelle Op. 204, Frohes Leben Op. 272 (3 Waltz Cycles)

Strauss, Josef

25,00 €

Josef Strauss – Die Spinnerin Op. 192, Die Libelle Op. 204, Frohes Leben Op. 272 (3 Waltz Cycles)

New print

(b. Vienna, 20 August 1827 — d. Vienna, 22 July 1870)

Concert Music

Volume 1

«Die Spinnerin»

polka française, op. 192

«Die Libelle»

polka mazur, op. 205

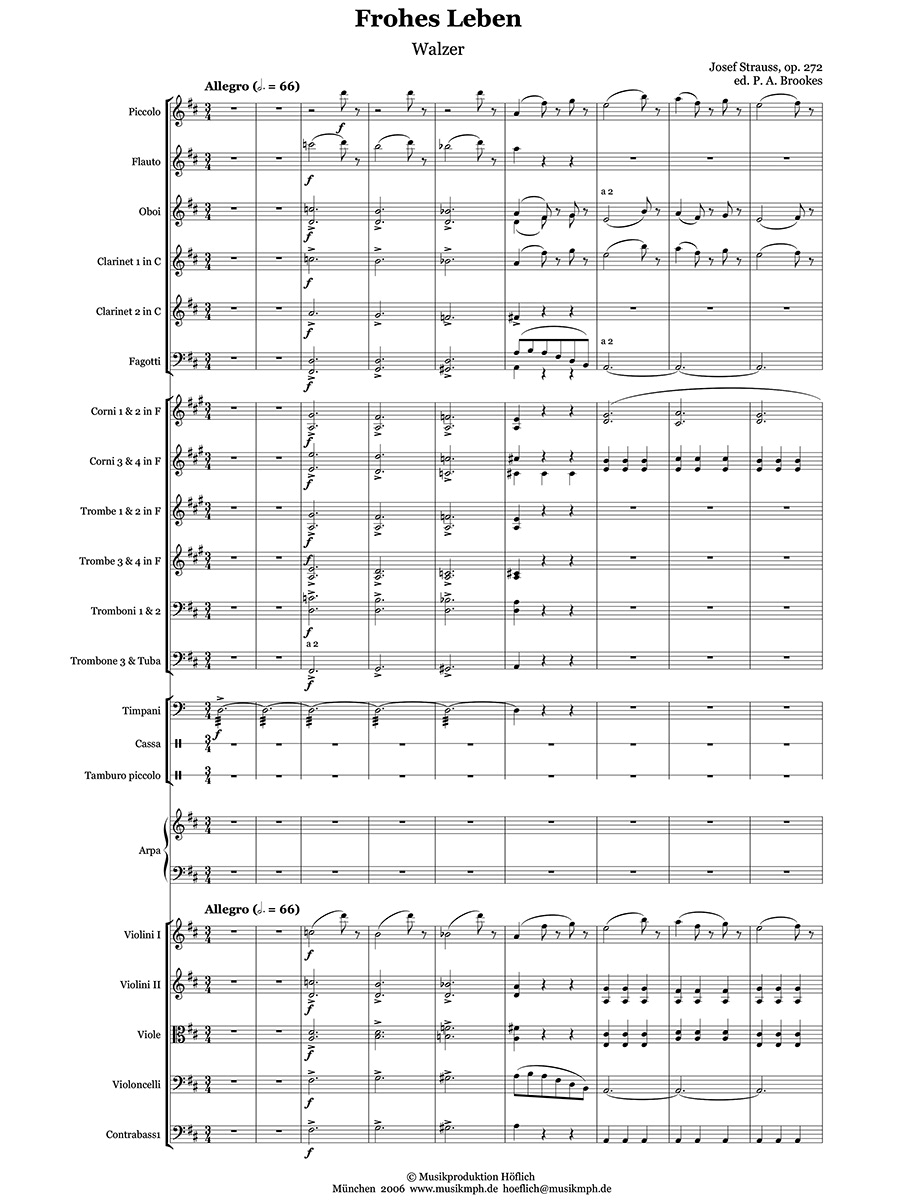

«Frohes Leben»

walzer, op. 272

It is likely that Josef Strauss – second son of Johan Baptist Strauss and Maria Anna Streim – suffered mild brain damage at his birth. It may eventually have caused his premature death at the age of 42, which followed his collapse whilst conducting. In any event, he suffered from spinal problems from a very early age, and was given particular care and attention by his mother. He was known to the family as ›Pepi‹ (his famous elder brother Johann II was ›Schani‹).

His own interests often differed from his family’s. In the revolutionary year of 1848, when his father’s and elder brother’s sympathies lay with the Hapsburgs, Josef obtained a uniform and rifle and headed for the barricades (he changed his mind when he learned that facing them was a Croatian regiment notorious for its uncompromising way with the students. He got rid of the uniform and weapon and went to a monastery for a few weeks; in the meantime, his mother diverted the attention of soldiers who came looking for him by providing plenty of beer!).

More prosaically, perhaps, Josef chose not to follow his father and elder brother into the family orchestra and music business. Instead, he qualified as an architect and civil engineer, and was engaged by the City of Vienna on the extensive rebuilding work that began in the mid-1800s. However, in 1853 he became sucked into the musical world when Johan II became ill and Josef was prevailed upon to direct the orchestra – just for part of one season. Pepi had resisted his family’s pressure for some time, but in the end gave in: »The unavoidable has happened«, he wrote to his fiancée, and he produced his first waltz, Die Ersten und Letzten (The First and Last), for the occasion.

Almost inevitably, one year later, Johan II took another break and Pepi stepped in again (with a new waltz: Die Ersten nach den Letzten – The First After the Last) and abandoned himself to a life of music. He even learned the violin to a sufficiently high standard that he could direct the orchestra in the manner of his father and elder brother, rather than use a baton.

More particularly, he produced a flood of music. Although his creative life lasted only seventeen years (1853–1870), he wrote well over 500 works, including arrangements of popular music of the day, as well as concert versions of music by contemporary composers, such as Mendelssohn, Schumann and, above all, Wagner (whose music he was – perhaps surprisingly – first to introduce to Vienna). His output was in fact greater than that of his two brothers, Johann II and Eduard, combined. Sadly, much of his music no longer exists; several unpublished or unfinished works disappeared after Josef’s death (a strong suspicion has fallen on Johann II, to the extent that some believe much of Die Fledermaus to be Josef’s music), and Eduard had the Strauss Orchestra’s entire library burned in 1907, which is known to have included 500 pieces by Josef. What we do have, though, are almost 300 pieces, most of which were published in Josef’s lifetime.

And what music it is! On one famous occasion, Johann II commented »Pepi is the more gifted of us two; I am merely the more popular«, and one can see what he meant. Within the limited dance forms that the Strausses chose to work with, Josef produced music that is often melodically and harmonically more interesting than one might expect, usually showing a sensitivity to orchestral colour that his more famous brother does not always match.

Die Spinnerin (The Spinner)

Josef wrote this for a concert at the Vienna Volksgarten Salon on 18 February 1866. The moto perpetuo of a spinning-wheel is reproduced by the cellos; the obvious model would have been the ›Spinning Chorus‹ from Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer.

Die Libelle (The Dragonfly)

This is one of Josef’s best-known works, a perfect little tone-picture of a dragonfly hovering over a pond in the summer heat. Of particular note are the accents that end (or begin?) each phrase, and which perfectly represent the way a dragonfly alters position as it hovers. The piece was written during the upheaval following the disastrous war between Austria and Prussia, with had ended with Austria’s defeat at Könnigrätz, and it was first performed on 21 October 1866 in the Volksgarten.

Frohes Leben (Joyful Life)

Composed in the summer of 1869, the title Frohes Leben is probably ironic, for this was no joyful time for Pepi. He and Johan II had travelled to Pavlovsk, near St. Petersburg, in order to obtain for Josef a contract to direct a season of concerts at the Vauxhall Pavillion there. The trip was not a success. Not only did no contract materialise, but Josef had made the mistake of forgetting about the difference between the Russian and Western calendars, so that the musicians all arrived 14 days early and needed paying! Josef wrote to his wife: »I shall have done very well if I manage to retain 1,000 roubles out of my fee of 3,000.« He became homesick and depressed, writing to his wife again, »I have to put up with many disagreeable things, but I accept them all, just to make possible a happy and carefree life for you. I work for you, for the sacrifice you have made by living in such poor surroundings these twelve years.« To cheer him up, his elder brother suggested they write a piece together. The result was the famous Pizzicato Polka, but it did not lift Pepi out of his depression. He wrote to his wife in September, »I don’t look at all well. I have become paler, my cheeks more hollow, I am losing my hair, I am on the whole very run down. I have no incentive to work … the uncertainty in which I live, not knowing whether I shall be engaged or not, makes me all the more ill and dissatisfied …« When it was eventually announced that Josef would not be engaged at Pavlovsk after all, he quickly produced a gallop Ohne Sorgen! (Without a Care!) and the waltz, Frohes Leben and returned to Vienna, where he gave the first performance on 14 November at the Sofiensaal. It is a fine waltz, with a real swing to it; no lengthy introduction or coda, just a stream of (almost) continuous happy thoughts. It achieves its good humour at least in part by the use of relatively short themes played at a brisk tempo. It is also a piece that benefits immeasurably from the da capo repeats in each waltz section, and this edition includes these in full. Frohes Leben is hardly known, but should be a standard, and it is a classic example of Josef’s ability to convey a particular mood or feeling, even when he did not necessarily share it.

About these editions

The editions of the three pieces in this volume (as well as those in all future volumes) are intended for performance, and full scores and parts are available from Musikproduktion Höflich, Munich (www.musikmph.de). They are based on the original orchestral parts, published – in the case of those in this volume – by Spina of Vienna. The following instruments, where they appear, are optional: oboe 2, bassoon 2, horns 3 & 4, trumpets 3 & 4, trombones 1 & 2 (but not 3), tuba.

Some editing has been necessary to produce performing editions easily understandable in the 21st Century. I have not detailed each editorial decision (these are not intended to be urtext editions), but here is a list of the principal matters that exercised me.

The music of all the Strauss family is full of short repeats, which always require time to sort out in rehearsal. I have tried to ease this burden by generally writing out da capo repeats in full. This is both for the sake of those reading these study scores as well as for players. In Frohes Leben, it is of particular importance, since orchestras do not always play the da capos in waltzes (although they are often clearly marked) and Frohes Leben benefits from having them.

There is not always agreement between parts in the matter note-lengths, especially at the ends of phrases; some parts have crotchets, others quavers. This is a feature quite common in Beethoven and Schubert, and may represent a convention by which the players played a note of roughly equal length, but neither crotchet nor quaver. I have made the parts consistent with each other within their family groups, but not necessarily between these groups, so that in bars 24 – 26 of Frohes Leben, the strings have quavers, but wind and brass have crotchets. In other cases, where bar after bar of typical waltz accompaniment is written in crotchets, but is used against a tune in quavers (bars 197 -210 of Frohes Leben, for instance), I have not made the accompaniment conform.

I have altered some phrasings to achieve consistency, usually among instruments of the same family, rather than between families.

One or two individual parts might have a crescendo or diminuendo (or, indeed, any expression mark) not shared by other parts. The issue here was whether the mark should apply just to that part, or to all parts, or to some but not others (and if the latter, then which ones). Josef Strauss often marked instruments at different dynamic levels, so that it was not always easy to guess. Where a solution is not obvious I have usually marked all parts the same, even if that has meant ignoring a single ›rogue‹ dynamic mark.

I have added a few tempo marks. These are usually at the beginning of works, and are fairly obvious (tempo di polka mazurka, for instance), though others are included as suggestions for successful performance (the animando in Frohes Leben). These tempo markings are in brackets and may safely be ignored.

More controversially, in Frohes Leben I have added short passages in the last few bars for timpani and harp. Josef Strauss’s expectation in this piece is that there would be two percussionists, one playing timpani and cassa (bass drum with cymbals attached), the other playing side drum. He clearly wanted the cassa sound at the end of the waltz, meaning that no-one would be free to play timpani. However, I have added a timpani part at the end in the event that an orchestra has a third percussionist available. As far as the harp goes, I have no excuse; it just seems a shame that the harpist has to sit mute throughout the finale. It goes without saying that these ›extras‹ are clearly marked and are optional.

Orchestral sets for these editions contain extra clarinet parts transcribed for clarinets in B flat or A (although this has sometimes meant minor adjustments to the 1st clarinet part to avoid going out of range). Also included are transcriptions of the trumpet parts for instruments in B flat. This is to ensure that these pieces are more easily playable by amateur ensembles. These extra instruments do not appear in the scores. Timpani and cassa parts are written on the same part, so that they can be played either by one player (as of course intended) or two.

Phillip Brookes, Market Drayton, 2006

Performance material is available at Musikproduktion Hoeflich, Munich (www.musikmph.de).

| Score No. | 620 |

|---|---|

| Special Edition | The Phillip Brookes Collection |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Pages | 116 |

| Size | |

| Performance materials | available |

| Printing | New print |

| Size | 160 x 240 mm |