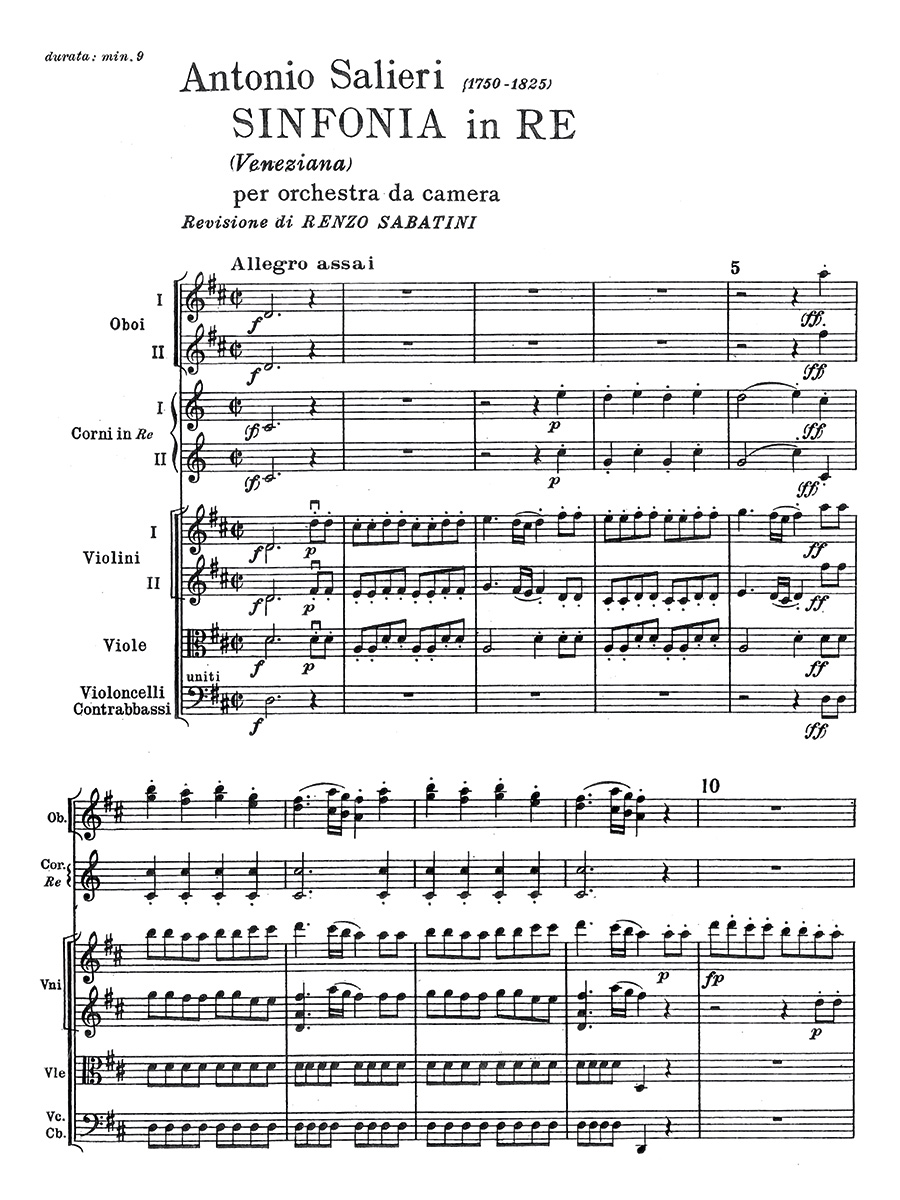

Sinfonia in Re “Veneziana”

Salieri, Antonio

16,00 €

Antonio Salieri

Sinfonia in Re “Veneziana” per orchestra da camera

(Symphony in D Major “Venetian” for chamber orchestra)

(18 August 1750, Legnago, Venetian Republic – 7 May 1825, Vienna)

Preface

This nine-minute work is scored for two oboes, two horns in D, and strings (two violins, viola, and cello/bass). The score was originally edited in 1961 by Renzo Sabatini for G. Ricordi (Milan); the nickname “Venetian” was added by the publisher, after the city where part of the music was first performed and Salieri’s own nickname for himself. The music for this three-movement work is partly adapted from Salieri’s overtures to La scuola de’ gelosi (1778) and La partenza inaspettata. Both were written during the three years Salieri spent in Rome, Venice, and Milan (1778-1780), following Joseph II’s reorganization of the Viennese court theatres with an emphasis on spoken drama.

This later Ricordi imprint of a later edition (Ricordi plate 130095) was also edited by Sabatini, with a few added bowing and “legato” markings; it dates from 1987. Sabatini reconstructed this three-movement chamber symphony from a set of printed orchestral parts he found in the Archive of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna. Dr. Hedwig Kraus, Director of the Archive in the 1960s, confirmed that the parts had been kept there since 1880, and that the cover read: “Sinfonia n. XIX del signor Antonio Salieri – Maestro di musica all’attual servizio de S. M. ‘Augustissimo Imperatore – Eseguita in Venezia.” The numerical designation “XIX” is likely to refer to a cataloging system in the Archive, rather than a title for the work.

The Sinfonia in D Major opens with an abbreviated sonata movement from La scuola de’ gelosi (The School of Jealousy), a two-act dramma giocoso that premiered in Venice in 1778; it was expanded for successful performances in Vienna (1783) and London (1786). The Viennese performances marked the debut of Joseph II’s new opera buffa troupe in the Italian theater. It was the only of Salieri’s operas to meet with continued success in Italy.

The central slow movement and concluding Presto both come from Salieri’s overture to La partenza inaspettata (The Unexpected Departure), a two-act intermezzo that premiered at the Teatro Valle in Rome during Carnival 1779. In all three movements, Salieri shows himself a competent master of Italian light opera style and an important predecessor to Rossini.

The Composer

Antonio Salieri was one of the most prominent Italian musicians in Europe during the Age of Enlightenment. He studied violin with his brother (a student of Tartini) and keyboard with a student of Padre Martini at Legnago Cathedral. Concertos were played in the local churches during both mass and vespers, and the young man formed strong opinions about the “solemnity” appropriate for organ music; he enjoyed traveling to church festivals with his older brother and even snuck off to one alone as a child. As an adult, Salieri often signed his name “Antonio Salieri Veneziano,” as he was born in Venetian territory and lived a year in Venice (aged sixteen, in 1766) after the death of his parents. While there, Salieri auditioned for the opera composer Florian Gassmann (1729-1774). Gassmann took him on as an apprentice, brought him to Vienna, and was soon described by Salieri as a father. The composer’s most successful work signed “Antonio Salieri Veneziano” was the 1779 intermezzo La partenza inaspettata.

Salieri married a Viennese and rose from an unpaid place in Emperor Joseph II’s private chamber ensemble to the capital’s most prestigious musical position, Royal and Imperial Hofkapellmeister (1788-1824). He served the Viennese court throughout his adult life, composing more than three dozen new grand operas for Vienna and Paris and acting as the personal music teacher to Joseph II. He was president of the Tonkünstler-Societät (to support retired musicians and their families) from 1788 to 1795, and produced its benefit concerts until 1818. In 1817, he became the first director of the music conservatory founded by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. Through Salieri’s private instruction in counterpoint and composition, three generations of Viennese composers such as Beethoven, Schubert (his pupil for eight years), Liszt, and Meyerbeer mastered elements of counterpoint and what we now characterize as “the Classical style.”

Salieri became a distinguished teacher of voice, coaching many of the star singers of his day and outliving Mozart and Haydn. Mozart wrote his comic Singspiel Der Schauspieldirektor as part of a 1786 contest with Salieri (who wrote an Italian comic opera for the occasion), and Mozart’s score pitted Vienna’s two leading coloratura sopranos against each other: Aloysia Weber (Mozart’s sister-in-law) and Catarina Cavalieri (Salieri’s mistress). Although frequently winning posts over W. A. Mozart, Salieri encouraged the younger composer’s efforts in orchestral music and passed several keyboard students on to him. In 1785, the two composers collaborated on a lost cantata for Anna “Nancy” Storace (the original Susanna in Figaro) entitled Per la ricuperata salute di Ophelia. In Mozart’s last surviving letter, he wrote to his wife that he collected Salieri and Cavalieri by carriage and drove them to see The Magic Flute: “He heard and saw with all his attention, and from the overture to the last choir there was no piece that didn’t elicit a ‘Bravo!’ or ‘Bello!’ out of him.” After Mozart’s death, Salieri gave free music lessons to Mozart’s younger son, Franz Xaver, and when he went to the 1790 Frankfurt coronation of Leopold II as Holy Roman Emperor, Salieri brought three Mozart masses as a gift.

During his fifty-year career at the Habsburg Court, Salieri composed over one hundred sacred works for the emperor’s chapel; these were continuously performed in Vienna for over a hundred years. Six masses survive: four orchestral, one a cappella, and one requiem mass. These complement his many smaller liturgical works (forty-five offertories alone) and dozens of non-liturgical pieces such as oratorios, cantatas, and concert arias.

Instrumental Music

Salieri enjoyed great prestige as a conductor and specialized in vocal works, but wrote no dramatic music during the last two decades of his life. He completed five concertos: two for piano, one for organ, and two concerti grossi. In Salieri’s own list of his compositions, he includes only two symphonies, but over two dozen serenades, cassations, and marches (both for wind ensemble and orchestra). When he first arrived in Vienna, he played chamber music three times a week with Emperor Joseph II, who preferred reading operas from open score to string quartets. The young Salieri was called upon to play keyboard, to sing alto in opera choruses, and to sing Italian arias.

As an apprentice to Gassmann, and later as a teacher, mentor, and “second father” to Joseph Weigl (son of Haydn’s principal cellist at Esterháza), he advocated composing small additions and replacements for larger existing works before embarking on full-length projects; this included composing replacement arias for other composers’ operas and orchestrating works for large orchestra.

Allegro assai mm. 1-190 D major tutti

Andante grazioso mm. 191-259 G Major strings only, violas briefly divide

attaca subito

Presto mm. 260-425 D Major tutti

Resources

Although Salieri’s personal papers and diaries have not been extant since before the composer’s friend Ignaz von Mosel wrote Über das Leben und die Werke des Antonio Salieri (1827), Rudolph Angermüller’s dissertation and two books

Recent well-documented books on Salieri’s music include Vittorio della Croce and Francesco Blanchetti’s Il Caso Salieri (Torino, 1994) and John A. Rice’s Antonio Salieri and Viennese Opera (Chicago, 1998). Salieri’s autograph scores and his numerous revisions are held by the Musiksammlung of the Austrian Nationalbibliothek. Many scores and parts include annotations by the composer, some written up to twenty years later. Many additional manuscripts and archives are held by the Haus-, Hof-, and Staatsarchiv and the Hofkammerarchiv in Vienna and Kärtner Landesarchiv in Klagenfurt.

Laura Stanfield Prichard, 2016

San Francisco Symphony and Boston Baroque

For performance material please contact Ricordi, Milano.

Deutsches Vorwort > HERE

| Score No. | |

|---|---|

| Edition | |

| Genre | |

| Size | |

| Printing | |

| Pages |