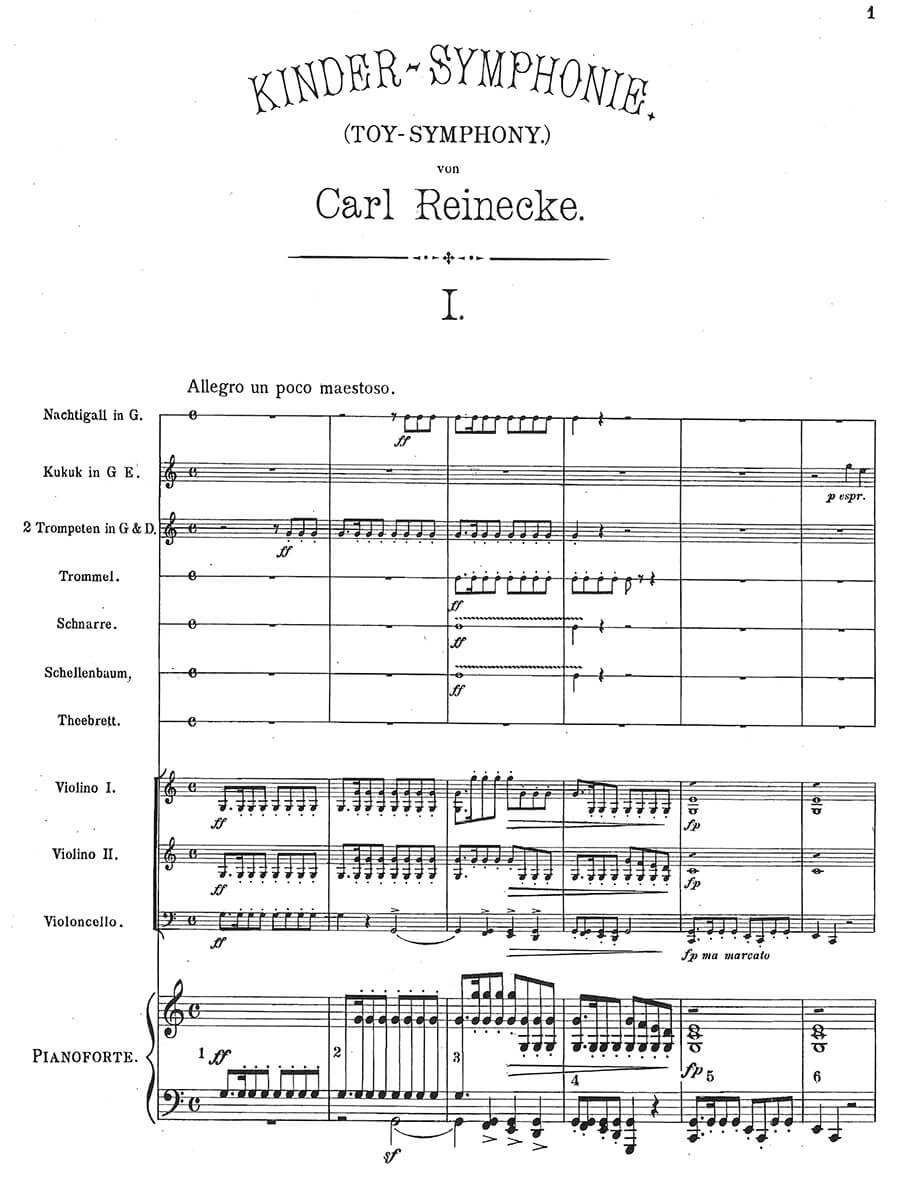

Toy Symphony in C major, Op. 239 for pianoforte, 2 violins, violoncello & 9 toy-instruments (score and parts)

Reinecke, Carl

25,00 €

Carl Reinecke – Toy Symphony in C major, op. 239

for pianoforte, 2 violins, violoncello & 9 toy-instruments (1895)

(b. Altona [Hamburg], 23 June 1824 – d. Leipzig, 10 March 1910)

I Allegro un poco maestoso (p. 1)

II Andantino (p. 13) – Poco più lento (p. 16) – Tempo primo (p. 17)

III Moderato (p. 20) – Un poco animato (p. 21)

IV Steeple Chase. Molto vivace (p. 23) Ancor più vivace (p. 30)

Preface

Carl Reinecke, one of the most prominent German composers in the generation of Bruckner and Brahms, is by no means uncontroversial among music historians. In an age of turmoil, from the revolution of Liszt’s “New German School” to the dismantlement of tonal harmony, he remained even in advanced age a guardian of tradition who staunchly upheld the ideals of a classicistic romanticism engendered by Mendelssohn and Schumann. By the age of six he was already taking lessons from his father Johann Rudolf Reinecke, and he gave his public début as early as 1835. He toured Europe as a solo pianist, earning a reputation as a “graceful player of Mozart.” From 1843 to 1846, thanks to a scholarship from the king of Denmark, Duke Christian VIII of Holstein (1786-1848) (at that time his native Altona, now a district of Hamburg, was the cultural capital of Schleswig-Holstein), he lived in Leipzig. There he became a protégé of Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), playing the latter’s Serenade and Allegro giocoso, op. 43, in the Gewandhaus on 16 November 1843. He also made the acquaintance of Robert Schumann (1810-1856), whom he deeply revered. It thus comes as no surprise that Mendelssohn and Schumann should become the lodestars of his own music; and when conversation later turned to his dependence on these two models, he could nonchalantly reply, “I would raise no objection to being called an epigone.”

In 1847 Reinecke was appointed pianist to the Danish court, but his stay there was short-lived: the outbreak of the First Schleswig War in 1848 forced him to return to Leipzig. This time, however, his luck abandoned him, and he moved to Bremen in 1849 to become a conductor. At the recommendation of Franz Liszt (1811-1886), he was invited to Paris by Hector Berlioz (1803-1869). There he gave concerts as a pianist and was reunited with Ferdinand Hiller (1811-1885), whom he had met earlier in Leipzig. In 1851 Hiller, now the director of Cologne Conservatory, invited him to join his staff as a piano teacher. Reinecke resumed contact with Schumann, now working in nearby Düsseldorf, where he also made the acquaintance of the young Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). From 1854 to 1859 Reinecke was a conductor in Barmen, which had long possessed a flourishing musical culture (today it is a district of Wuppertal). He then became music director in Breslau (now Wrocław).

Hardly had Reinecke settled in Breslau than he received an offer to take charge of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. It would become the position of a lifetime, and he held it for twenty-five years from 1860 to 1895. He also functioned as a professor of piano and composition at Leipzig Conservatory at a time when a flood of highly gifted composers from all over the world moved there to put the finishing touches on their craft. Among his students were such leading figures as (in chronological order by date of birth) Max Bruch, Johan Severin Svendsen, Arthur Sullivan, Edvard Grieg, Hugo Riemann, Hans Huber, Charles Villiers Stanford, Iwan Knorr, Leoš Janáček, George Chadwick, Julius Röntgen, Christian Sinding, Ethel Smyth, Karl Muck, Emil Nikolaus von Reznicek, Isaac Albéniz, Frederick Delius, Robert Teichmüller, Felix Weingartner, Cornelis Dopper, Hermann Suter, Eyvind Alnæs, Gerhard von Keussler, Julián Carillo, Richard Wetz, Mikolajus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, and Sigfrid Karg-Elert.

Following his quite abrupt and humiliating dismissal from the Gewandhaus (he was succeeded by Arthur Nikisch [1855-1922], who ushered in a new era far more brilliant than the suave Reinecke years and shaped the orchestra into an ensemble of international stature), Reinecke headed Leipzig Conservatory from 1897 to 1902. He remained ceaselessly active until late in life, becoming the first pianist to record a piece on the Welte-Mignon player piano in 1905 (the Largo from Mozart’s Coronation Concerto), performing Mozart’s Concerto for Two Pianos in 1906 with his student Fritz von Bose (1865-1945), and continuing to give concerts in the Gewandhaus as late as 1909. Besides his orientation on Mozart, Mendelssohn, and Schumann, his piano writing also betrays influences of Chopin and Brahms. His orchestral music is unquestionably dominated by the legacy of Mendelssohn and Schumann; strikingly little of the power and sweep of Beethoven left an impression on him, even though he made a deep and lifelong study of that master’s piano sonatas. Today Reinecke the composer is best-known for having written concertos for two instruments severely neglected by the great masters of the romantic era: the Harp Concerto in E minor (op. 182) and the Flute Concerto in D major (op. 283), the latter being published in 1908. Undine, his sonata in E minor for flute and piano (op. 167), likewise remains popular, and recently string orchestras have found his very beautiful Serenade in G minor of 1898 (op. 242) to be a welcome addition to a genre so ingratiatingly cultivated by Robert Volkmann (1815-1883), Dvořák, Grieg, Tchaikovsky, and Robert Fuchs (1847-1927).

Reinecke composed not only four piano concertos but also four symphonies. The first, in G major, was written in 1850 and performed several times between 1850 and 1858; however, he declined to give it an opus number and later refused to acknowledge it (today it is no longer extant). His authorized symphonies thus begin with Symphony No. 1 in A major (op. 79), premièred in Leipzig on 2 December 1858 (version 1) and later in the same city on 22 October 1863. It was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1864. Reinecke’s other two symphonies arose in connection with his position as Gewandhaus conductor. Symphony No. 2, in C minor (op. 134), originated in 1874 and was issued in full score, parts, and two-piano reduction by the Leipzig publisher Robert Forberg in 1875. Finally Symphony No. 3, in G minor (op. 227), was completed in 1894 and published by Simrock two years later.

In 1895 Reinecke wrote a four-movement Toy Symphony (op. 239) that was published by Augener & Co. of London that same year and made use of a number of toy instruments. Proclaiming it to be a “carnival jest” he naturally declined to give it a number and thus to acknowledge it as a fully-fledged symphony. Among its many borrowings and allusions are the following, all found in the second movement: Brüderlein fein by Wenzel Müller (1759-1835), Sehnsucht nach dem Frühling (K. 596) by Wolfgang Amadé Mozart, melodies from Carl Maria von Weber’s Oberon and Ludwig van Beethoven’s Septet (op. 20), and Weber’s Last Waltz (the fifth piece from Danses brillantes, op. 26) by the fashionable romantic composer Carl Gottlieb Reissiger (1798-1859). The score is prefaced with introductory words from the composer. Ever since its publication the Toy Symphony, in its faux-simplistic jocularity, has been one of Reinecke’s most frequently heard compositions.

Translation: Bradford Robinson

For performance material please contact Simrock, Hamburg.

| Score No. | 1843 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Specifics | |

| Pages | 88 |