The Hymn of Life (Hymnus an das Leben) for mixed choir and orchestra

Nietzsche, Friedrich

12,00 €

Friedrich Nietzsche

(b. Röcken, 15. October 1844 – d. Weimar, 25. August 1900)

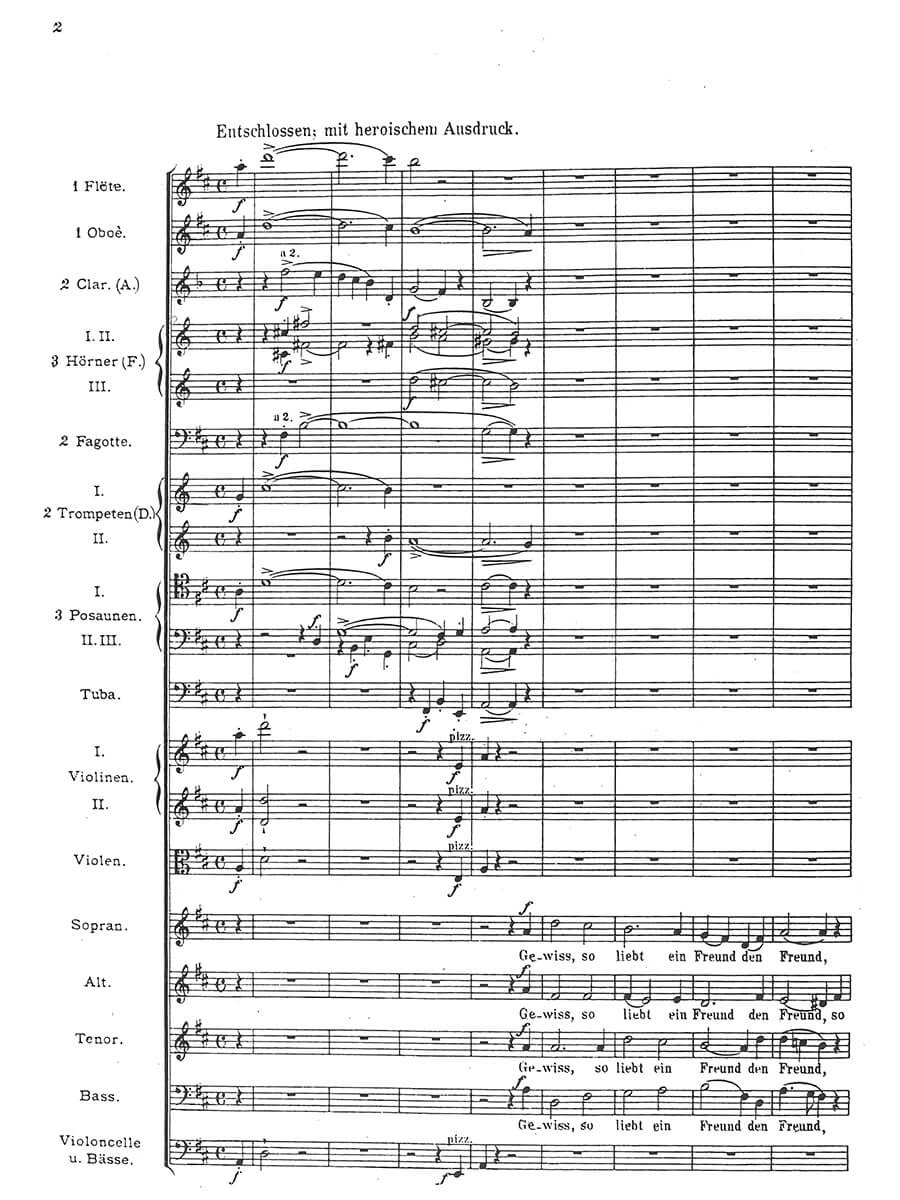

The Hymn of Life (Hymnus an das Leben)

for mixed choir and orchestra

Preface

Music was of uttermost importance for Friedrich Nietzsche. Not only did he find a subject for philosophical reflection in music, but he also considered it a medium for the expression of his own personal artistic inclinations.

Born in 1844 near Leipzig in the home of a Lutheran pastor and an organ player, Nietzsche had an early contact with music. He was obviously profoundly influenced by protestant church music from the young age. Later, during his time as a student of Naumburg Gymnasium, he often attended soirees at the house of his acquaintance Gustav Krug, where he was strengthened in his conviction that music was his vocation. While these musical evenings introduced him to many contemporary composers, he still developed an affinity for German classics. The first pieces he composed at the age of 14 were in fact influenced by Schubert and Mendelssohn, as well as by Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. He considered these authors to represent the “soul of German music” and remained loyal to them until his discovery of Wagner. While he struggled with Wagner’s influence, by the time he fully embraced him Nietzsche already had composed most of his musical work. His musical interests and compositional skills further grew through his engagement with the private club “Germania”, which he founded in 1860 with Krug and Wilhelm Pinder. Musical composition, essayistic writing, as well as debates on subjects of contemporary culture and music with the “Germania” club, all had an effective impact on the personal development of the future German philosopher. During these early years of intellectual maturation Nietzsche went through a phase of national romanticism, but his interest in nationalism exceeded the German people. He developed an interest in nordic mythology, the legends of Gothic King Ermanaric, Serbian folklore and epic poetry, Hungarian and Polish national music. It is also worth mentioning that although Nietzsche critically approached his composing, often inspired by these and other themes, he never managed to produce any longer or more complex pieces. Most of his work were short piano, or voice and piano compositions, with the exception of Wie sich Rebenranken schwingen (1863) and Eine Sylvesternacht (1864), both violin and piano pieces, several pieces for piano four hands, for vocal quartet and for choir (Kirchengeschichtliches Responsorium, 1871). Nevertheless, Nietzsche wrote and fantasized about grand and important work, having set Schopenhauer as a lasting philosophical standard. Schopenhauer wrote that: „(…) music is by no means like the other arts, namely a copy of the Ideas, but a copy of the will itself, the objectivity of which are the Ideas. For this reason the effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence.” Through Schopenhauer, to whom he will eventually dedicate a book (Schopenhauer als Erzieher, 1874), Nietzsche came closer to Wagner, who was also fond of Schopenhauer. The two men finally met in 1868, before Nietzsche was awarded a teaching position at the University of Basel as well as a honorary doctorate by the University of Leipzig. In Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde Nietzsche recognized exactly those things Schopenhauer wrote about. Between 1868 and the Nietzsche contra Wagner essay (written 1888-1889, published in 1895) the two men will go to develop and break up a complex intellectual relationship. However, it seems that Wagner was essential for Nietzsche, who was heavily influenced by him, as well as his previous exploration of classic Greek culture, to develop the two-fold concept principle of Apollonian and Dionysian. This philosophical principle is indubitably crucial for understanding his relationship to arts.

During this time his music never caught up with his philosophical work, so this dialectic principle cannot be attested in his compositions. At the very end of his musical career Nietzsche (who realized during his studies that music will remain his passion, but not his vocation) managed to produce a single piece which stands out from the rest of his oeuvre in quality and intellectual prowess – Hymnus an das Leben (The Hymn of Life).

Hymnus an das Leben was based on the musical theme from his own Hymnus auf die Freundschaft (1874), a piano piece that Wagner was familiar with. The Hymn of Life was finished in 1887 using a 1882 poem Lebensgebet by Lou Salomé, whom by this time he already met. Writing on Salomé Nietzsche said: „I found no more gifted or reflective spirit. Lou is by far the smartest person I ever knew“. Her Lebensgebet (The Prayer of Life) tells of unconditional love for life, regardless of the challenges life puts before man. With this topic in mind, as well as the fact this was Nietzsche’s last musical work, it could be called a sort of a philosophical testament. “The Great Cynic” of the 19th century managed to speak of life worth living just before his own psychological illness and death.

The hymn was composed for mixed choir and an orchestra, but the unskilled Nietzsche needed help with the arrangement, which was provided by Johann Heinrich Köselitz (1854-1918). Nick-named Peter Gast by Nietzsche, Köselitz was a friend and a close collaborator since the 1870s up until Nietzsche’s death. He left himself a modest opus, with only notable work being the comic opera Der Löwe von Venedig. However, Köselitz was credited for his collaboration on Nietzsche’s music as well as for his later work (criticized by some) on Nietzsche’s Weimar archive. There is no doubt that Köselitz was responsible for developing, and possibly even amending, the original score. Distinctly developed vocal parts dominate the piece; the atmosphere is solemn, with light harmonies and often repeated euphonious theme, while the orchestra plays a somewhat modest part in the harmonic background. A short introduction in D major is followed by two verses, after which the hymnic musical theme is repeated. Simple, transparent structure, as well as a memorable melody, create a specific, rather wistful musical image.

In Ecce Homo Nietzsche writes that he composed this piece during a period of profound “tragical pathos”. He found some consolation in Salomé’s poetry, which tells how “Pain is not a worthy objection to life.” In the same essay the German philosopher says he hopes that after his death the Hymnus an das Leben will be “sang in his memory”.

Radoš Mitrović, 2017

| Score No. | |

|---|---|

| Edition | |

| Genre | |

| Size | |

| Printing | |

| Pages |