Miscellaneous Works for Orchestra: Fest-Vorspiel / Künstlerfestzug zur Schiller-Feier 1859 / Festmarsch zur Goethe-Jubiläum-Feier / Huldigungsmarsch / Vom Fels zum Meer (Deutscher Sieges-Marsch) / Ungarischer Sturmmarsch / Die Toten (Funeral Ode for orchestra and male choir) / Die Nacht

Liszt, Franz

46,00 €

Franz Liszt

(b. Raiding, 22 October 1811 – d. Bayreuth, 31 July 1886)

Miscellaneous Works for Orchestra

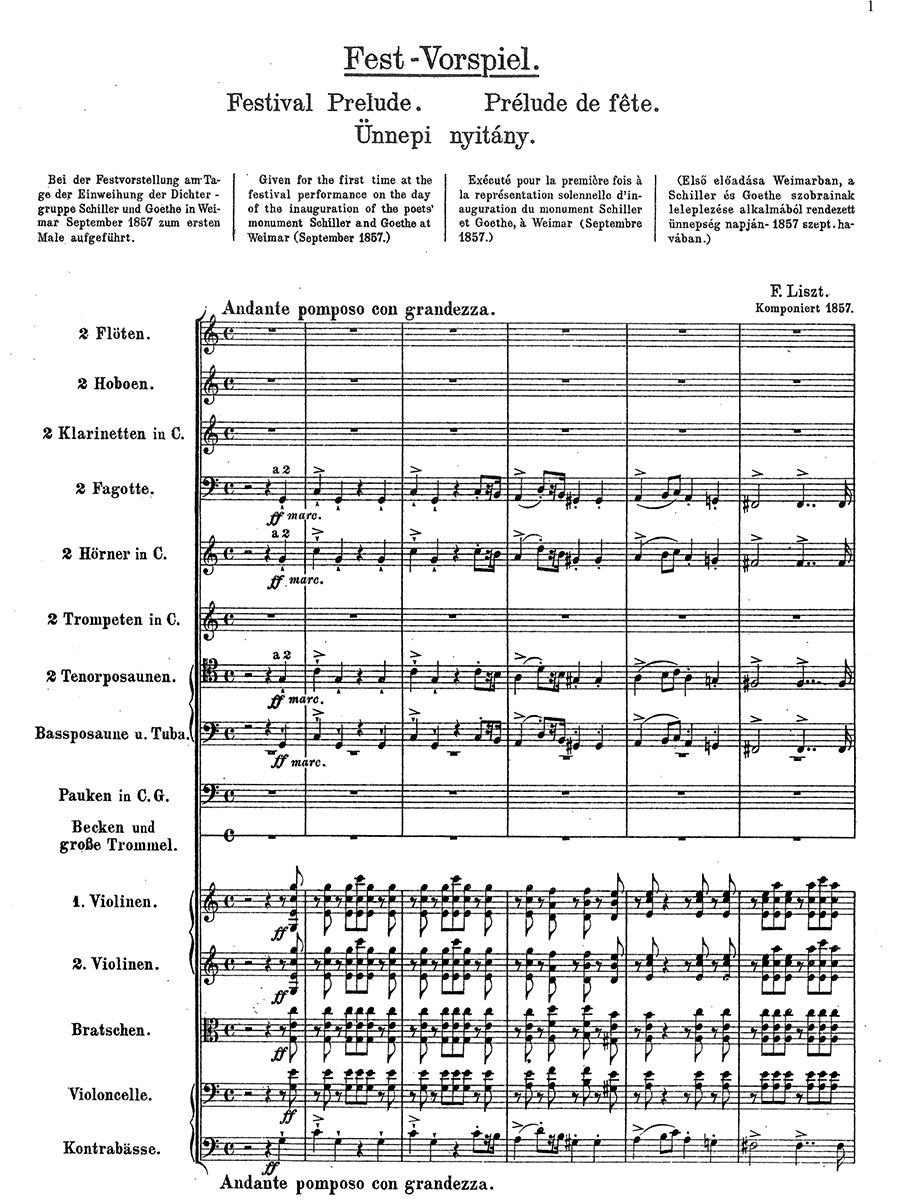

Fest – Vorspiel p. 1

Künstler – Festzug zur Schillerfeier 1859 p. 17

Festmarsch zur Goethe – Jubiläum – Feier p. 55

Huldigungsmarsch p. 89

Vom Fels zum Meer. Deutscher Siegesmarsch p. 113

Ungarischer Marsch zur Krönungsfeier in Ofen -Pest am 8 Juni 1867 p. 135

Ungarischer Sturmmarsch p. 157

Die Toten. Funeral Ode for orchestra and male choir p. 187

Die Nacht p. 211

Preface

Of Franz Liszt’s hundreds and possibly thousands of compositions, arrangements, and transcriptions, none are less familiar to the general public than his orchestral marches. (The sole exceptions may be his secular works for unaccompanied men’s voices.) The music included in the present volume nevertheless represents three important aspects of Liszt’s creative career: his willingness to compose “occasional” works, his near-obsession with re-composing and -arranging most of his output, and his enthusiasm for certain aspects of Hungary, her peoples, and her history.

As it happens, almost all of the works in question—the Festvorspiel (Liszt omitted the hyphen) for the inauguration of a monument dedicated jointly in 1857 to Friedrich Schiller and John Wolfgang von Goethe, two of Weimar’s greatest poets; the “artist’s processional” march composed for a different ceremony in honor of Schiller; the march composed for the coronation of Franz Joseph I (already Emperor of Austria) as king of Hungary; and so on— began life as keyboard compositions, or survive as keyboard arrangements and transcriptions, or exist in alternate orchestral versions. There are two iterations of the Huldigungsmarsch (again, no hyphen), both dating from the 1850s. The Goethe and Schiller festival marches also survive in several versions.

Nor is all of the present compositions entirely original or at least unique. Vom Fels zum Meer may have originally been composed for the piano. Or maybe not; we simply do not know. The same holds true for the Huldigungsmarsch, which also survives in an unpublished version for wind band. The Festvorspiel, on the other hand, did begin life as a piano piece. And so on. The Küstlerfestzug zur Schillerfeier makes use of themes from Liszt’s An die Künstler as well as Liszt’s symphonic poem Die Ideale. Hungaria, another symphonic poem, incorporates material previously composed for the Heroischer Marsch im ungarischen Styl, a piano piece dedicated to Fernando II, then King of Portugal! Clearly Liszt considered his marches and Hungarian works worthy of at least some late-life attention. This, together with the fact that he confessed in 1863 to a “passion for variants, and for what seems to be ameliorations of style”: a passion that had long ago taken hold of him, and that became stronger as he grew older.

What else to say, then, of the occasional compositions reprinted in the present volume, all of them belonging to an age in which ceremonial music was far more popular than it is today? Like much of his music, keyboard as well as orchestral, they tend to be loud, befitting their purposes and settings; several were or at last have been performed out of doors. Perhaps for these reasons most of Liszt’s biographers have ignored them. In his excellent survey of the composer’s life and character, Derek Watson doesn’t even mention most of Liszt’s marches. Alan Walker discusses several of the occasions for which a few of them were composed, but as music he pays them no attention at all. They seem to have struck Humphrey Searle, the English composer and scholar, as little different from the conclusion of Tasso: Lamento e trionfo: a passage he proclaimed “Liszt at his most bombastic.” For Searle, these “other works for orchestra”—works other than the symphonic poems—needed “little discussion.”

More intriguing, especially for Hungarian performers and scholars, are those works associated with events in the history of the Magyar peoples. Here issues of nationalism and Liszt’s self-proclaimed Hungarian patriotism come to the fore. This is a much more complex subject than can be considered here. Suffice it to say that a great many of his works incorporate something “Hungarian,” be it titles (the five Historische ungarische Bildnisse, for example, also appeared under the title “Magyar történelmi arcképek,” and each of them bears the name of a political or literary leader), or folk tunes, or melodies borrowed from pre-existing popular Hungarian pieces, or tropes and gestures associated with the verbunkos idiom—the last sometimes discussed as one aspect of the so-called style hongroise…

(Michael Saffle, 2017)

Read full preface / Komplettes Vorwort lesen > HERE

| Score No. | 1930 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 232 |