Ball-Suite for orchestra, Op. 170

Lachner, Franz

40,00 €

Franz Lachner

(b. Rain am Lech, 2 April 1803 – d. Munich, 20 January 1890)

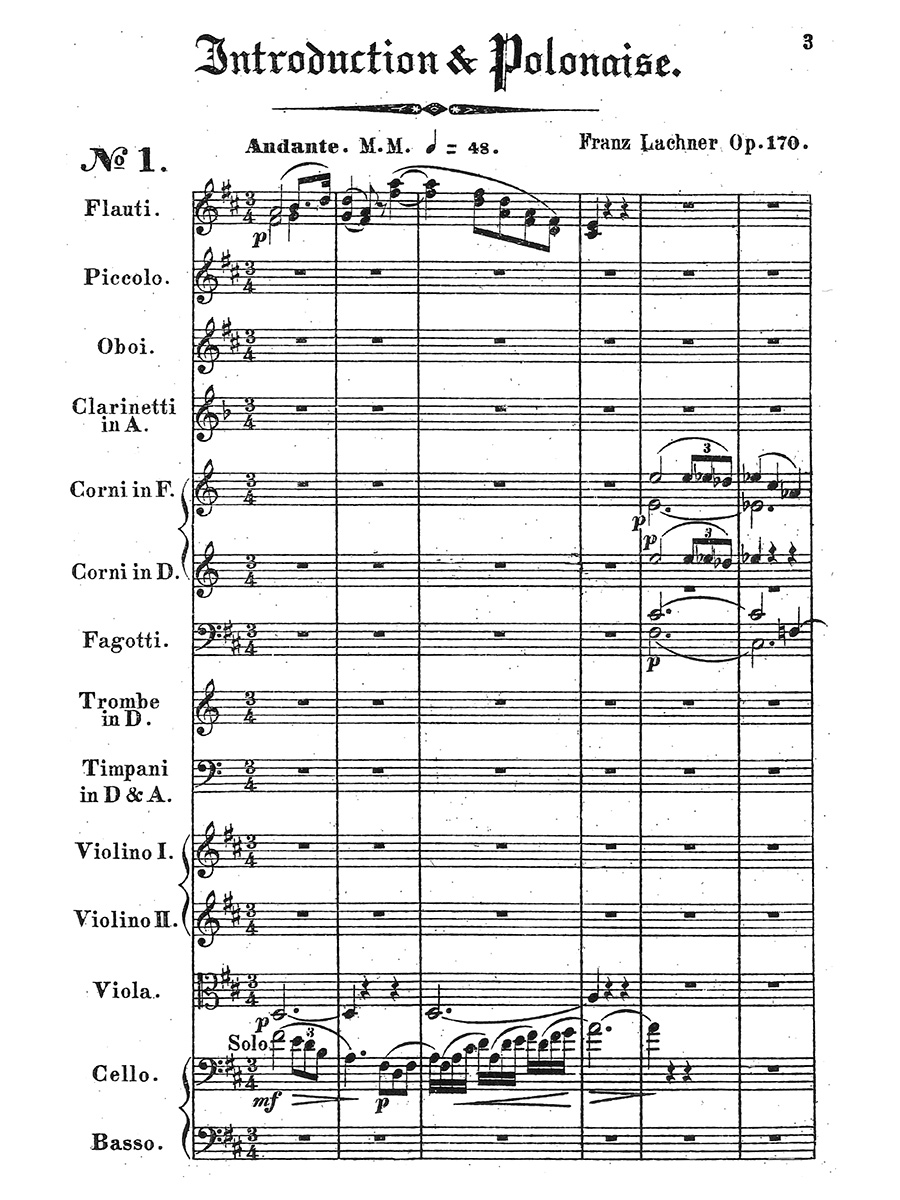

Ball-Suite for Orchestra Opus 170

Preface

Franz Lachner came from a prodigiously musical family where all progeny, both male and female, were organists. Their father, Anton Lachner (1756-1820), was a horologist and played the organ and violin; Franz played the organ, violin, cello, horn and double bass.1 His first teacher was his father but he later studied with Caspar Ett, Simon Sechter (1788- 1867 who taught Brahms’s teacher, Eduard Marxsen, and Anton Bruckner) and Abbé Maximilian Stadler (1748-1833, a friend of Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert). In 1823 he won a competition to become the organist at the Evange- lische Kirche in Vienna.2 Whilst in Vienna he became friends with and drinking companion3 of Schubert and his circle which included the painter Moritz von Schwind.4 He also met Beethoven through the piano factory of Andreas Streicher.5 Lachner held other important posts in Vienna, becoming first assistant conductor at the prestigious Kärntertortheater, then principal conductor in 1829. In 1834 he went to Mannheim for two years as Kapellmeister, then in 1836 to the court opera in Munich where he remained for thirty years. He was also the director and leader of the Musikalischen Akademie and director of music at the Königliche Vokalkapelle there.6 In 1864 he was supplanted by Hans von Bülow at Wagner’s request and retired in 1868. He was fêted during his life being awarded a Ph.D. from the University of Munich in 1863 and Freeman of the City in 1883. Josef Rheinberger (1839-1901) was one of his pupils.7 All this gives a picture of a man who frequented the highest musical circles and who was thoroughly trained in his art. His own output consisted of 8 symphonies (1828? -1855?), 7 large orchestral suites (1861-1881), 4 operas, organ music, songs, church music, string quartets and chamber music for various ensembles.

As a person he was generous, recommending Wagner for the Royal Maximilian Order in 1864 and then successfully in 1873.8 The oft related comments about him by Wagner ‘ein vollständiger Esel und Lump zugleich sein’9 (a complete ass and scoundrel) are contradicted in recently published letters showing Wagner as friendly and sufficiently intimate to invi- te himself to lunch, calling Lachner ‘Hochgeehrtester Freund!’ (most honoured Friend).10 It is mostly in Cosima’s diaries that disrespect is seen, where he is mocked for writing Suites and not keeping strict tempi.11 Wagner was keen that Hans von Bülow conducted his Tristan und Isolde and persuaded Ludwig to appoint Bülow as Court Kapellmeister for Special Services,12 but it was only through Lachner’s years of technical work with the orchestra that they could play this opera. To show in how high esteem he was held, to celebrate his twenty-five years at the Munich court opera Moritz von Schwind made the 12.5 metre long Lachnerrolle – a series of sketches celebrating his life and work. This was the first time Schwind had attempted to show a personal artistic history through pictures.13 On Lachner’s retirement the poet Eduard Mörike said “mein alter Freund Lachner ist pensioniert worden und mit ihm alle gute Musick”14 (my old friend Lachner is now pensioned off and with him all good music).

Lachner was very famous in his day and his works were regularly performed. His experience as a string and brass player enabled him to write fluently for these instruments and his fine orchestration was noted by the contemporary critic Eduard Hanslick who said Lachner had “glänzende technische und formelle Vorzüge” (brilliant technical and formal qualities) and “Meisterschaft der Instrumentierung” (mastery of orchestration).15 As a composer he was melodically and harmoni- cally conservative, but his inventiveness as an orchestrator creating rich tapestries of orchestral colour, his contrapuntal skill and his originality in handling formal structures set him apart. He had an innate dramatic sense of climax both in terms of timing and aural intensity.

Franz Lachner “was the first to awaken the sleeping suite to new life”16 as it had fallen out of favour during the Classical period even though Mozart, Haydn and Schubert wrote sets of dances. Lachner’s Suites have many baroque movements including some non-dance forms such as fugue, march and variations, however, his Ball-Suite Op. 170 of 1874 has six

“modern” movements with none of the baroque forms: Introduction and Polonaise, Mazurka, Walzer, Intermezzo, Dreher and Lance. The keys of the suite hover around third and relative minor relationships D major/F-sharp minor/B minor/G major/E minor-E major/B minor-D major. Lachner’s trade mark use of sequences, imaginative and varied orchestration (especially during repetitions) and form are features of this piece. Most sections are marked to be repeated although this is rarely executed in modern performances.

The slow Introduction and Polonaise features an opening solo cello melody which when repeated a third lower, the accompaniment is placed a fifth higher with the concluding bars re-orchestrated. The florid solo flute passage which concludes the Introduction introduces the dotted rhythm featured in the subsequent Allegretto. The Polonaise is an “art” Polonaise, an instrumental development of the original dance form which uses greater rhythmic variety and looser form …

Read full preface written by Dr F. Jane Schopf, Rose Bruford College, 2016 > HERE

| Score No. | |

|---|---|

| Edition | |

| Genre | |

| Size | |

| Printing | |

| Pages |