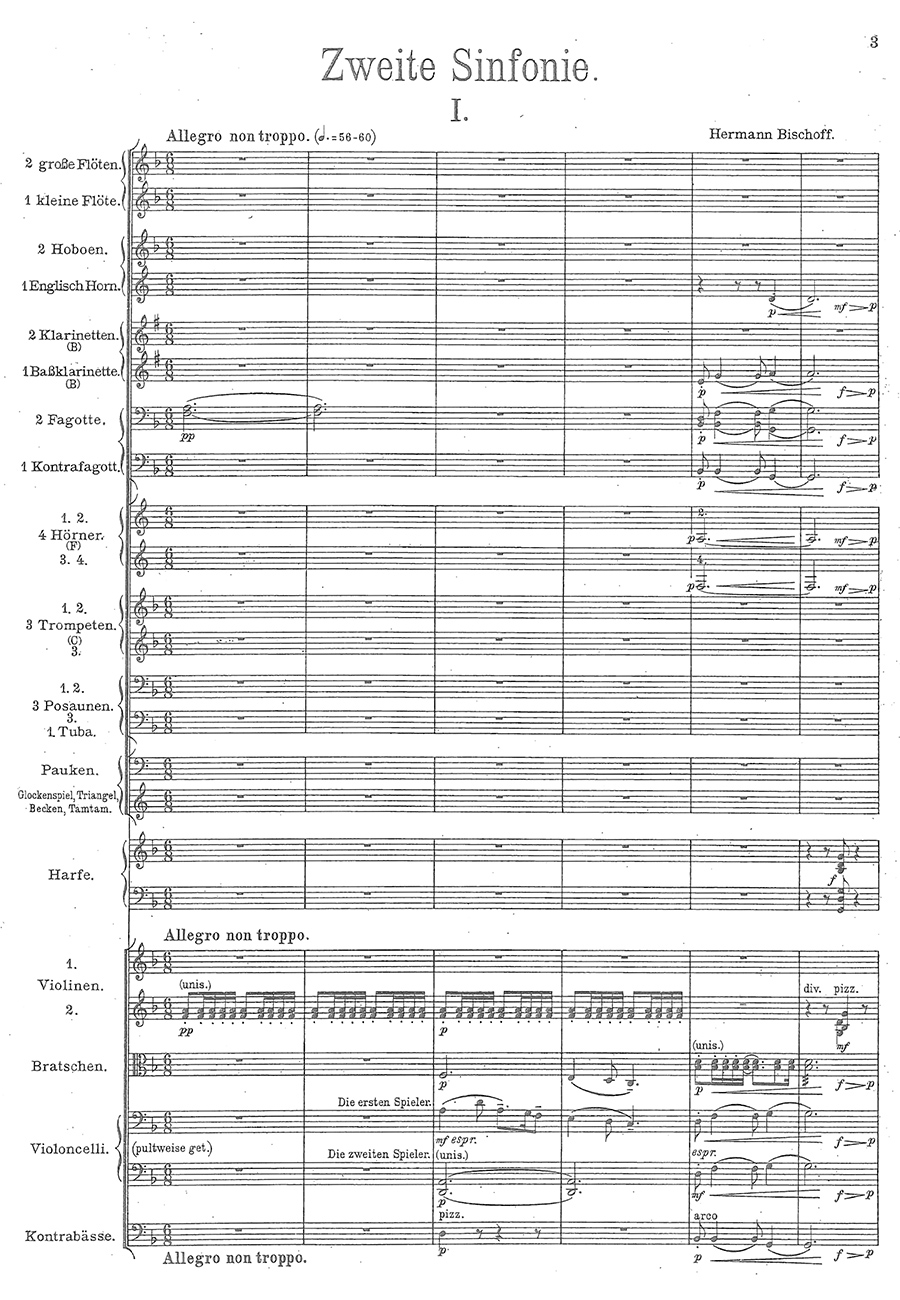

Symphony No. 2 in D minor

Bischoff, Hermann

34,00 €

Hermann Bischoff

Symphony No. 2 in D minor (1910)

(b. Duisburg, 7 January 1868 – d. Berlin, 25 January 1936 in Berlin)

Preface

It would be wrong, if true to the facts, to view Hermann Bischoff mainly as Richard Strauss’s sole pupil. True, his friendship with Strauss helped one or another of his works to reach performance (he dedicated his First Symphony to the elder composer in gratitude), and it was Strauss who arranged for him to receive a secure position with the Berlin Copyright Society after the onset of the Great Depression. But Bischoff was not primarily, much less exclusively, a professional musician. Born into an affluent family of Duisburg industrialists, he first studied at Leipzig Conservatory before settling in Munich in 1888. Though he gradually drew attention with pieces in various genres, he was mainly a man of independent means and frequented Munich’s literary and artistic circles in this capacity. In 1898 he married the painter Marie Himmighoffen. He was on friendly professional terms with virtually every member of the Munich school of composers associated with Ludwig Thuille and Max Schillings, and was Strauss’s regular partner in the favorite German card game known as Skat.

In early 1911 Bischoff’s Symphony No. 2 in D minor, completed the previous year, received its première in Hamburg under the baton of Siegmund von Hausegger – an event probably resulting not least from Strauss’s intercession. (Eckhart van den Hoogen, in his CD booklet, quotes extensively from the surviving documents on this work.) The otherwise quite critical Heinrich Chevalley gave the work a thoroughly warm reception in a detailed review published in Die Musik:

“Bischoff’s First Symphony was a work deeply indebted to Richard Strauss, being written to an unstated but surely extant and well-defined program. Compared to this loud and agitated music, which sought to tell us of grand inner experiences, his new D-minor Symphony seems almost like an idyll. It is a piece composed in the spirit of absolute music, and thus evinces a far greater emphasis on formal proportions and an avoidance of ultimate and sublime refinements of expression. It has little or nothing to tell us about the horrors and pangs of artistic creation and seems to have sprung into existence entirely on the bright side of life. This time the mighty pinnacles which make us feel released in exalted solitude from earthly burdens and leave us closer to Eternity – all those great and ultimate things – are not Bischoff’s theme. He traverses the small purlieus of tranquil feelings, eschewing convulsions and paroxysms and becalming the surface of the waters. On the basis of its ideas, one is almost tempted to call this piece a sinfonietta or a suite in the grander style, all the more so as the movements which usually witness the decisive struggles in a symphony – the first movement and the finale – hardly deserve being considered fully symphonic in their essence and structure. The finale in particular, with its gently lilting themes and rhythmic motion, provides no basis for sustaining the proud and crowning edifice of a symphony. Nor does the opening movement actually transcend the level of a suite, preferring instead to spin a ballad-like idea without making the least attempt to tighten the musical tension, and dispensing with the attractions of tonal contrast, not from a want of skill, but from some sort of poetic intent. Of the middle movements of this blithely and fluently fashioned piece, which has gratifyingly freed itself from the clutches of the octopoidal Straussian embrace, the intermezzo movement towers far above the andante. Whereas the latter, descending alarmingly deep into the lowlands of bloated operatic pathos, fails to generate a unifying mood, the intermezzo charmingly and gracefully evolves into a savory interplay of highly characteristic profile-lines ingeniously harmonized and orchestrated. This movement, reminiscent of the galanterie of the rococo era, of Pierrot Lunaire, was sufficient to ensure the success of a work which the listeners had until then followed with cautious skepticism.” …

Jürgen Schaarwächter, 2015

| Score No. | |

|---|---|

| Edition | |

| Genre | |

| Pages | |

| Size | |

| Printing |