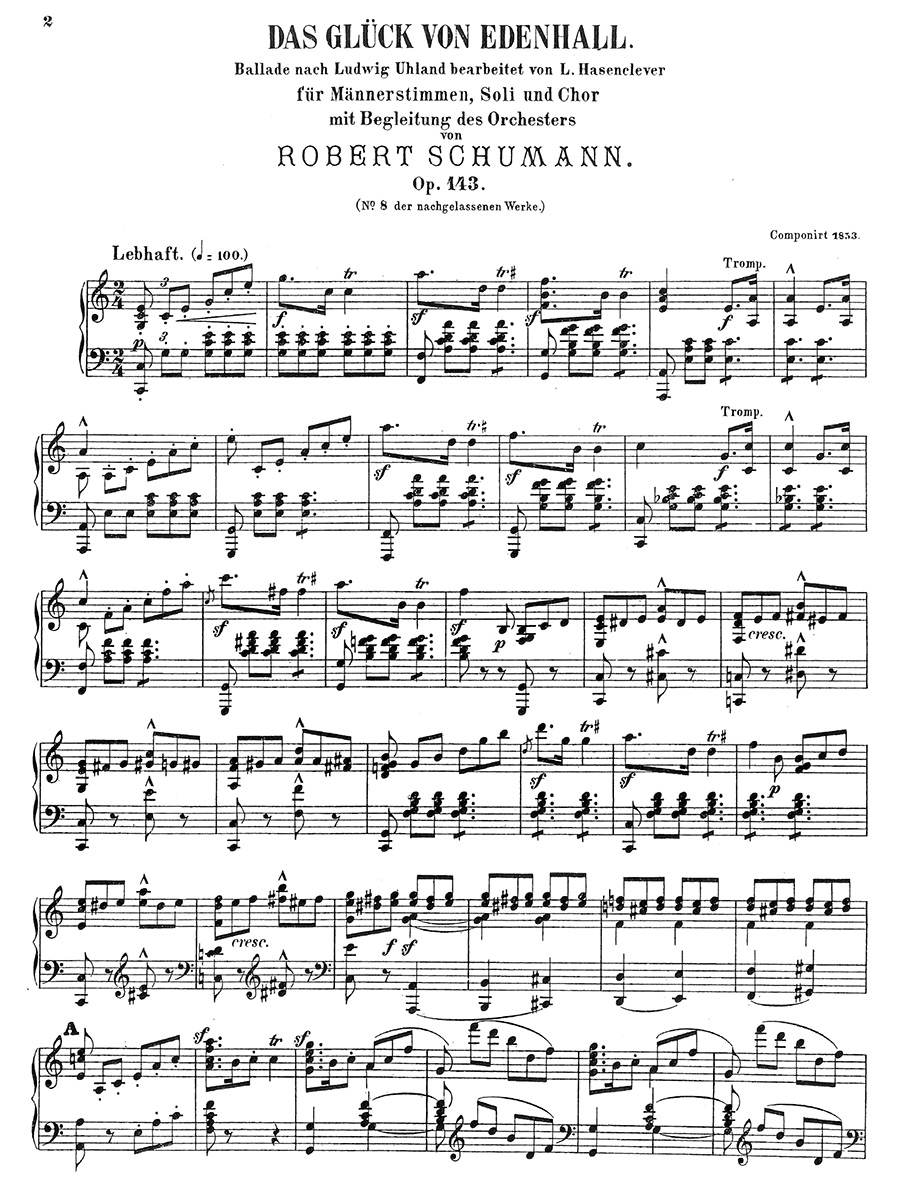

Das Glück von Edenhall Op. 143 for solo voices, male chorus and orchestra (Vocal Score)

Schumann, Robert

12,00 €

Schumann, Robert

Das Glück von Edenhall Op. 143 for solo voices, male chorus and orchestra (Vocal Score)

For information on the piece read the preface to the full score:

Das Glück von Edenhall, choral ballad for solo voices, male chorus and orchestra, op. 143, text by R. Hasenclever after a poem by Ludwig Uhland (1853)

Perhaps no nineteenth-century genre has suffered more from the social upheavals of the modern age than the choral ballad, a tradition once firmly upheld by a network of middle-class amateur choral societies, glee clubs, and semi-professional orchestras and cultivated by composers of the stature of Brahms (Rinaldo, Schicksalslied, Alto Rhapsody), Bruckner (Helgoland), Mendelssohn (Erste Walpurgisnacht), and above all Robert Schumann, whose several contributions were long considered to be pinnacles of the genre. With the disappearance of these institutions – and with them the fondness of the educated classes for narrative poetry in a faux-naïf folk style – much superior music of the romantic age was consigned to oblivion and still awaits rediscovery.

Schumann’s choral ballads fall at the end of his career, when he was employed as a choir conductor in Düsseldorf. Foremost among them are the three large-scale settings of ballads by Ludwig Uhland: Der Königssohn, op. 116, Des Sängers Fluch, op. 139, and Das Glück von Edenhall, op. 143, all accompanied by full orchestra, and all dealing with the passing of old societies and the emergence of new ones. Uhland (1787-1862), a self-consciously patriotic poet of international repute, was a favorite among Germany’s middle classes, who saw in him a reflection of their own anti-monarchic tendencies. With the failure of the 1848 revolutions and the re-entrenchment in Germany of a narrow militaristic conservatism, the aspirations of the middle classes could find an outlet in art that was denied them in the political arena. Even Schumann, a man otherwise wholly disinterested in the historical events of his time, could respond to this new situation in his immediate social surroundings.

Uhland’s poem tells the cautionary tale of a young aristocrat who has inherited, along with his castle Edenhall and its domains, a mysterious crystal goblet on which are inscribed the portentous words: “The Luck of Edenhall.” At a banquet the young lord challenges Fate by filling the goblet and causing it to ring like a bell, at which point it shatters in his hand. At that very moment his enemies storm the castle. All perish in the general conflagration except the trusty seneschal, who has warned his lord all along and must now see his world reduced to ashes.

Schumann, however, did not set Uhland’s text verbatim, but had it adapted by one R. Hasenclever to take on a slightly different twist. Instead of a loss of Paradise, as is suggested by the very name of “Edenhall,” the revised poem now ends in a rousing hymn of victory by the triumphant forces, thereby forming a satisfying counterweight to the festive banquet chorus of the opening. Whether musical or interpretive reasons were paramount in Schumann’s mind, the result is a recasting of the original poem into a celebration of the passing of the old and the arrival of the new. (It is perhaps interesting to note, as a comment on the British national character, that Uhland based his poem on item no. 19 from Ritson’s Fairy-Tales, in which the trusty seneschal catches the goblet before it can shatter.)

Das Glück von Edenhall was written in 1853 shortly before Schumann’s descent into madness. In the few years remaining to him the work did not appear in print. The first edition, a vocal score identified as “No. 8 of the posthumous works,” was issued by J. Rieter-Biedermann of Winterthur, Switzerland, in 1860. It was quickly taken up by English choral societies, who were already familiar with Uhland’s “Luck of Edenhall” in a well-known translation by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The work was published in vocal score by Novello in 1875 and again, with a simplified piano part, in 1895. The extent of its popularity before the First World can be gauged from the fact that Novello issued yet another vocal score in 1911, this time in tonic sol-fa notation to capture an ever wider musical clientele.

Bradford Robinson, 2005

Performance material: Breitkopf und Härtel, Wiesbaden

| Partitur Nr. | |

|---|---|

| Edition | |

| Genre | |

| Format | |

| Anmerkungen | |

| Druck |